The Materials Department is pleased to announce the hiring of three stellar new faculty, who, we know, will continue the legacy of excellence that has been recognized for more than thirty years. You can get to know a little about them below.

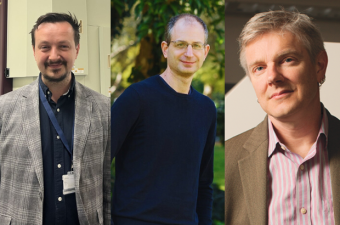

Photo (L-R): G. Mazur, E. Berg, S. Billinge

Simon Billinge, Professor, Materials

Director, California NanoSystems Institute

Simon Billinge joins UCSB as a professor of materials and as the new director of the California NanoSystems Institute (CNSI), taking over for materials professor Craig Hawker, who has served in that role since 2013. He has spent the past seventeen years as a professor of applied physics, applied mathematics, and materials science at Columbia University and, prior to that, more than a decade as a professor at Michigan State University.

Billinge makes extensive use of advanced x-ray and neutron-diffraction techniques to study local-structure property relationships of disordered crystals and nanocrystals, and their role in informing the properties of diverse materials relevant to, for example, energy, catalysis, environmental remediation, and pharmaceuticals. Billinge also employs neutron- and electron-scattering methods, as well as advanced computation and analysis, including artificial intelligence, machine learning, and graph theoretic methods.

A fellow of the American Physical Society and the Neutron Scattering Society of America, Billinge, says he came to UCSB for several reasons: “I like change and crave new experiences, and this was a perfect moment in my career to explore such a change into a new location with new colleagues and a new leadership role. I was happy at Columbia, so the list of jobs I would have left it for was small. The CNSI position has all the characteristics that make it an exciting change.”

As a physicist Billinge describes the close association between the Physics and Materials Departments at UCSB as “a strong attractor” for him, adding, “From my undergrad days, my training was in materials science, but I fell in love with physics in grad school and wanted to get a faculty position in a physics department.” He describes his move to the Applied Physics Department at Columbia as natural, because it allowed him “to do more applied work without dropping the basic science, thus bridging the physics and engineering aspects.”

He says that he is “super-excited to to have the same kinds of opportunities at UCSB, noting further that “having strong applied mathematics and computer science on campus, as well as the Computational Science Center, which is co-run by CNSI, also presents a perfect platform to develop collaborations and seek ways to blend math, physics, and materials science and develop tools for the whole community.”

Like many others who have come to UCSB, Billinge says, “The ocean and UCSB’s proximity to it are really a high point for me,” adding, “When I was young, I had to choose between two careers: joining the UK's Royal Navy or going into academics. It was a hard choice, because I really wanted to sail around the world and visit interesting places.”

Billinge was also attracted by what he describes as “the dynamite combination of the quality of the UCSB faculty and their research coupled with a strong focus on collegiality. “I am a very collaborative researcher, and I immediately knew that I would feel at home here,” he explains. “This focus on collaboration breeds community and positivity, and this was so evident during my visits to campus. It is surprisingly hard to find at other places at such an institutional level.”

As someone who has cultivated close relationships with his colleagues, Billinge says that the hardest thing about leaving Columbia was “the impact my decision has on other people who are slightly collateral damage: my students and postdocs,” which is why, he adds, “Much of my current focus is to make sure that they come out of it in a positive way, and that I accommodate their needs as best as possible.”

Given the administrative duties that come as CNSI director, Billinge says that he is “crafting a small direction change” in his research while maintaining active participation in that work and in mentoring graduate students and postdocs.

“I am known for developing scattering methods to study disorder in materials and its effect on their properties. We apply the methods we develop to many different materials and scientific problems related to everything from pharmaceuticals to quantum materials and even ancient art and cultural objects. I’m very excited about collaborating widely with folks at UCSB as I continue to do this.

“Recently, with my applied mathematics hat on, we have been applying AI and ML to this task and I have learned about where these methods can be effective — and where less so,” he continues. “I am interested in using these approaches to address the problem of predictive synthesis and synthesizability. For instance, given a material you want, what recipe or synthesis protocol will give it to you, and how can we integrate this into the workflows of researchers at CNSI? This will be a bit of a departure for me, but I think the collective benefits will be good if we can make it work.”

Coming to UCSB as a mid-career faculty member, Billinge explains, “It has been on my mind that, over the years, my research has been helped enormously by larger-scale infrastructures and programs that were built through the efforts of others. I am thinking of national facilities, like synchrotrons and large-scale funding programs that underpin such efforts. I felt that at this stage of my career it was important to give something back in that way. The administrative component makes the CNSI role attractive; more importantly, I see the opportunity to build infrastructure and programs that can benefit many people, as I have benefited. But also, it is still embedded in a faculty-research environment, so I won’t have to give up the science I love to do."

Erez Berg, Professor, Materials and Electrical & Computer Engineering

Mehrabian Endowed Presidential Chair

Erez Berg was attracted to UCSB, he says, by “the world-class program on quantum materials, and the proximity of the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics, which brings the top minds in the field to the area every year,” adding, “The beautiful scenery and the ocean didn't hurt, either.”

Berg has conducted creative and influential theoretical studies to gain valuable insights into quantum materials, which embody quantum physics phenomena that cannot be fully explained by classical physics. He works to improve understanding of novel topological phases of matter, identifying unique electronic properties of materials arising from the special geometries, or topologies, in which the electrons arrange themselves.

"Topological superconductors are a fascinating example of how intricate behavior can emerge in a system of many interacting quantum particles,” he says. “They really are a gift from nature. However, they have turned out to be extremely rare in the wild and not easy to engineer in the lab. In recent years, new promising candidate topological superconductors have been discovered in two-dimensional materials, so I remain optimistic.”

Berg’s recent work has had a significant impact on a broad swath of important questions in the field, especially in two new directions. He spearheaded a novel method that made it possible for the first time to realize topological phenomena in an otherwise non-topological quantum system. He did so by applying an external driving force, which led to immediate experimental implementations in real materials. He also led the theoretical search for new physical platforms for topological superconductors that show promise in terms of storing and manipulating quantum information.

Berg has received numerous high accolades, most notably the Blavatnik Award for Young Scientists in Israel in 2019, when he was recognized for developing novel theoretical and computational tools to study long-standing and emerging questions in quantum materials. He earned a PhD in physics from Stanford University, and he completed postdoctoral training at Harvard University. Prior to UCSB, he spent five years as a professor in the Department of Condensed Matter Physics and five years working as a senior scientist at the Weizmann Institute of Science, in Israel.

“The field of ‘anything quantum’ has exploded in recent years, which has been fascinating to follow,” he notes, adding, “There is no doubt in my mind that, hype aside, we will see 'practical' quantum devices within the next decade or two. It’s too early to say how far-reaching the implications of quantum will be, but I think it's certainly a worthwhile scientific endeavor.”

As a theorist, Berg notes, “There are many groups I look forward to collaborating with at UCSB. Interacting closely with experimentalists who are designing and measuring new quantum materials is essential for my work. I have had a long-term, ongoing collaboration with [physics professor] Andrea Young's group on two-dimensional quantum materials, and look forward to working with materials professors Susanne Stemmer and Stephen Wilson, and, of course, other theoretical groups.”

Gregorz Mazur, Assistant Professor, Materials

Gregorz Mazur came to UCSB after serving as a lecturer in the Department of Materials at the University of Oxford and spending nearly two years in industry after serving as a postdoctoral researcher at the Research Institute for Quantum Computing and Quantum Internet (QuTech) in the Netherlands. His recent work has involved developing new material systems, as well as measuring and fabricating techniques to realize solid-state topological (p-wave) superconductors.

“UCSB offers a unique environment for people who are working at the intersection of semiconductors, materials science, mesoscopic physics, and quantum computing,” Mazur says in describing what brought him to campus. “It not only hosts the world-famous Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics, which gives faculty a chance to interact with the best theorists from the entire world, but the College of Engineering itself is home to a world-class nanofabrication facility that engages local industries and enablies researchers to work at the cutting edge of modern physics and quantum technologies. The importance of this cannot be overstated, as many places around the world aspire to having a similar ecosystem; and UCSB is among the few that succeed. Finally, it's really hard to find a better place for somebody like me, who works on quantum hardware, with both Google Quantum AI and Microsoft Station Q having their headquarters in Goleta.”

Mazur describes his research as lying at “the intersection of experimental condensed-matter physics and materials science,” where, he says, “I'm trying to engineer phases of matter that are otherwise difficult to find in nature or whose existence is obscured by other phenomena. Some of those phases of matter are particularly exciting, because they could, in principle, allow for quantum bits that are protected from decoherence and errors at the hardware level.”

He says he is excited about working with his new UCSB colleagues as he focuses his research on germanium/silicon-germanium (SiGe) quantum wells, which are compatible with modern industrial semiconductor processing and hold a promise of bringing quantum devices to scale. “I'm especially looking forward to working with [materials professors} Chris Palmstrøm and Susanne Stemmer on engineering these new material systems, as well as bringing my expertise to the platforms they're pursuing,” he says. “I'm also keen to engage with [materials professor and Institute for Energy Efficiency director] Steve DenBaars to set up a SiGe growth effort here at UCSB. I'm also looking forward to engaging with [fellow new faculty member] Erez Berg on the theory of topological quantum devices. My hope is to stay connected, too, with my colleagues from the Physics Department, Professor Andrea Young and [new Nobel laureate] Michel Devoret. Finally, it's hard to overstate the role of shared facilities such as the low-temperature lab in the Materials Research Laboratory (MRL) characterization center, which allows access to world-class electron microscopy.

Mazur finds excitement in the relative youth of the global quantum enterprise. “Quantum is still young enough that the next big leap might come not from a product roadmap, but from a lab notebook,” he notes. “We don’t yet have the quantum equivalent of the transistor — a universally accepted building block that’s scalable, manufacturable, and robust across many use cases. And that’s exactly why academic research still matters so much. Universities are set up to explore ideas that look strange at first, to take technical risks, and to follow results wherever they lead.

“We’ve already seen how surprising the field can be,” he continues. “Platforms that were once considered niche can suddenly show unexpected advantages, sometimes in scaling, sometimes in control, sometimes in the path to error correction. That’s a reminder that we shouldn’t assume that the ‘winning’ architecture is already obvious. The most valuable breakthroughs often come from people asking fundamental questions that don’t fit neatly into a short-term deliverable. In that sense, I think it’s entirely plausible that the ‘quantum transistor’ — the key primitive that makes large-scale systems feel inevitable — hasn’t been found yet, and could still emerge from university research.”

Mazur is also keenly interested in the link between academia and industry. “I’m genuinely excited by what industry is doing,” he says. “Industrial teams are turning prototypes into engineered systems to improve fabrication, packaging, control stacks, calibration, and reliability, and, crucially, holding performance accountable with rigorous benchmarks. That kind of disciplined iteration is essential, because even the best scientific idea becomes transformative only when it can be built and operated at scale. The most encouraging picture, to me, is the combination of academia expanding the frontier of what’s possible, and industry rapidly converting the most compelling ideas into platforms we can test, compare, and, ultimately, use.”